Location: Vientiane, Laos

Tuesday finally came. The hospital sent word to the Australian embassy that the biker was stable, conscious, and even up for a visit at Vientiane’s military hospital. Jack scheduled an appointment with Jody to visit him the next afternoon. Jody and the embassy’s translator, Phvong, would accompany Jack to help with negotiations.

I couldn’t help but wonder what they were negotiating. The price of a man’s life? Laos’s tourist tax? What was this awful accident worth to the biker, to the Australian Embassy, to Jack? Being the curious creature that I am, I asked if I could come along and hopefully observe some of the madness. What sort of bureaucracy and corruption would we encounter at the embassy? At the hospital?

I also needed to witness the biker walking and talking to rid myself of the nightmarish visions that were haunting me, the vivid flashes of him lying limp in the road.

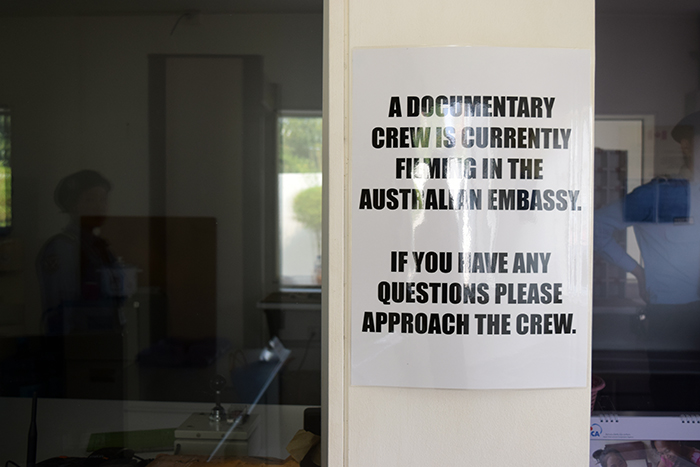

The embassy was well guarded. Steel fences with spikes held up by white concrete pillars. A guardhouse at the entrance with metal detectors, plastic signs describing what you could and could not carry into the building, and two security guards in fresh-pressed uniforms. I hadn’t brought my passport (my own personal safety measure), and they wouldn’t let Jack or me into the building without identification until Jody finally rang and confirmed the appointment. I dropped my camera and cell phone into a metal bin that slid out under the glass screen that separated myself from the guards. My electronics were replaced with a plastic name tag on a lanyard.

I walked through the metal detectors, out the guardhouse door, and stepped into a place in such stark contrast to Vientiane’s dusty streets that I had the ridiculous thought that I’d maybe wandered into a Dr. Seuss picture book illustration.

I was surrounded by a luscious garden which led up to a huge, teeth-brightening-ad-white building. The grass was laughably green, and upon seeing the number of sprinkler heads peeking up between the neon-y blades, I dissolved into giggles of disbelief. Everything glittered that starry, dewy glitter of fresh water droplets. It was the greenest place I’d seen in Laos so far. Vientiane itself was brown from the cracked sidewalks to the muddy riverside to the crumbling buildings. But here, tropical plants, including curved palm trees and red and purple birds-of-paradise flowers, lined the path, which was a mix of manufactured, decorative pebbles sealed together by concrete.

And when we entered the embassy building/palace, it wasn’t just clean, it was immaculate. I felt bad when I pushed open the glass doorway with my fingers; someone would probably have to wipe that down immediately. The lobby was decorated in spotless, new, contemporary-to-modern style furniture. There was glass everywhere, from the large windows overlooking the too-green yards to the balcony overhanging the first floor. I could see through it to the square, leather lounges up above us.

We met Jody and the film crew in a windowless side room with a wooden table surrounded by swiveling office chairs. The crew recorded Jody going over the next steps with Jack. We found out the biker’s name was Meksavanh Pathoummakong and that he had been recommended by doctors to remain hospitalized for at least the next day or so. When Jack saw Mr. Pathoummakong he should voice his concern for the man, his family, and the accident. He should keep calm at all times. Though Jody couldn’t take part in anything dealing with money (Australian law), Phvong would act as a go-between for Jack and the biker. Everything should be fine as long as everyone played their parts.

But could Jody really know what was going to happen when we met the biker? I couldn’t tell if her aura of calm was for the cameras only.

I wondered what angle The Embassy was looking for. Did the editors want the audience to vie for Jack’s innocence? Young Australian involved in brutal accident falls victim to police corruption and blood money scam. Or were they looking for a villain? Careless Australian pedestrian vacationing in Laos involved in motorbike accident walks away, local man hospitalized with serious injuries.

The film crew took multiple shots of me nodding as Jody spoke and I wondered what part I played. Would I get a title in the script?

Cassia, 23. Jack’s Friend and Fellow Backpacker.

Or maybe it’d just be a mention, my bobbing head a most minor character in the script.

Friend of Jack.

Maybe I’d just be cut entirely. I preferred that, actually. I had come on this visit as an observer, as a support system for my friend. It was strange thinking for once I’d be at the mercy of editors instead of editing someone’s story.

It was also difficult for me to reconcile the experiences of our past few days with what was in front of me: Jody’s clean, red, polyester uniform, the disposable, plastic cups of water they kept offering us as we sat there during the briefing (we were informed it was fancy filtered tap water, not from a bottle at the supermarket - the first drinkable tap water we’d encountered in Southeast Asia), and the classic, office-building fluorescent lights that turned us all that sickly shade of not-quite-natural-lighting-yellow. How could this place exist only a few hours from the village where we’d been left so helpless on the side of the road, trying frantically to revive an unconscious man and waiting forty-five minutes before a police officer arrived and flagged down a random military truck to take him to a hospital?

Well, if I’d learned anything from the past few days, it was that life can be as strange as it is brief.

When the camera had been turned off and Jody and the crew had left the room, I noticed Jack’s face had paled. He was looking down at his untouched cup of complimentary water.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

“Yeah, yeah. I just want to see that he’s okay.”

“He is! The hospital said he is.” I put on a cheery tone, placed a comforting hand on his shoulder, and hoped that I sounded more confident than I was.

“I’m really nervous about all this.”

“It makes sense that you’re nervous. Everything’s going to be okay, though. Jody and Phvong totally know what they’re doing.” More fake confidence.

“Yeah.” He looked like he might be sick.

Jody, Phvong, two embassy drivers, the producer, the camera man, Jack, and I all hopped into an unmarked van and headed to the hospital. When we sat down, the camera man informed us we had to wear seat belts. Otherwise, they weren’t legally allowed to film us. I fumbled with mine; it was the first time I’d worn a seatbelt in months. Jack and I exchanged an amused look over the idea of vehicular safety on these Laotian roads. Jody sweat through her uniform dress and grumbled that the film crew insisted she wear it, even though she usually never did outside the air conditioned office. We laughed at how preposterously formal it made her look. As we rode through the city, the crew asked everyone to act serious and took shots of us staring silently out the car windows.

The hospital was a large complex of multi-story buildings surrounded by men in green and beige military uniforms. No cameras allowed there, either. When we wandered into the first door we came across, a doctor pointed us back a few hundred meters to one of the last buildings on the edge of the square. Mrs. Pathoummakong met us at that entrance. She wore a shiny, embroidered chartreuse skirt and matching blouse and her hair hung in a long, thick ponytail down her back. She smiled and waved as we approached. It was a distinct change from the last time I’d seen her, half-sobbing into tissues at the police station, pointing at us and crying out “farang, farang.” I felt good about it, though. Maybe it meant her husband really was okay.

She led us through the building, which was small, a maze of narrow hallways littered with shoes. Several pairs were identical to the ones the biker wore on the day of the crash. All black, nondescript, cheap. Rubber bottoms, short laces like loafers. A bit scuffed on the edges and creased around the topside from constant wear. I couldn’t look at them too long without remembering how one of them had slipped off that day and tumbled down the road, Mr. Pathoummakong’s foot left only in a navy sock.

Everything seemed old, but maybe that was because I’d just come from the Australian embassy. All the rooms had windows facing the hallways and I could see through the smudged glass and the open doorways that each one was filled, corner-to-corner, with stretchers and bodies. People even lounged in the corners of the floor. Several fanned themselves with woven bamboo. There were no hospital gowns; everyone was just wearing their day-to-day clothes. I couldn’t tell the difference between patients and visitors. There also weren’t any doctors or recognizable medical equipment around. It seemed more like a holding area than an actual hospital, and maybe that’s what it was.

We slipped through a crowded room of metal stretchers and bored-looking patients and I almost tripped over the foot of a scrawny, elderly man crouched beside the door. His jeans and t-shirt were gritty and his toenails were brown and chipped. I nodded my apology and he grinned back at me, totally toothless. We entered a back room where the biker lay. His wife claimed a spot behind his stretcher and faced everyone.

Mr. Pathoummakong’s lip was stitched up, but otherwise I couldn’t see any external injuries. He waved when we entered the room and asked which one of us he’d hit. When Phvong pointed to Jack, he shook hands with him, still laying flat on the bed. He wore shorts and a red-and-white striped polo.

It was a strange scene: all six of us lined up in a semi-circle around the bed. There was only one other occupant of the room, an unidentified woman in a traditional green dress who sat crosslegged in her stretcher. I leaned back against the metal bar of her bed while Mr. Pathoummakong, Phvong, and Jack spoke. She and I watched everything play out.

Phvong translated as the biker described his injuries, still laying flat, his eyes peering down his nose at us, and gesturing with his hands.

“He says the doctors say he may have injured his brain from how fast he hit the ground. Like his brain moved when he hit. He had an MRI and they said it’s all okay, but he still can’t sit or stand up without experiencing dizziness.”

We all nodded.

“He says they don’t know how long he has to stay in the hospital, maybe a long time. They have to see how he recovers.”

Mr. Pathoummakong showed us his lip, which was swollen and sewn back onto his face. It had eleven stitches keeping it in place. The messy black x’s of string looked painful, crude.

Jack asked Phvong to translate, “I hope you’re well and I understand the stress that you and your family are going through.”

“He says it means a lot that you came here to the hospital see him.”

Jack stood with his hands twisted together in front of him. All of the pleasantries were making me nervous; everyone was waiting for the same moment. Why not get it over with? I noticed the camera man for The Embassy was secretly shooting footage on his iPhone. I was torn. I wanted to smack it out of his hand; he hadn’t asked anyone for that coverage. But the journalist in me appreciated the undercover effort.

Footage inside a Laotian military hospital? Nice.

“How do I ask how I can help?” Jack asked Phvong.

“He says you can help with the medical bills since he hasn’t been able to work. There are many costs at the hospital. He had to pay for transportation to the first hospital, and then for when he was transferred to this hospital. He also says the MRI cost 900,000 Kip…but yesterday he told me that it only cost 800,000. I am not sure what the actual price is, now.”

Mr. Pathoummakong continued rattling off expenses and Phvong’s cheer took a downward spin, and a frown etched across his features.

“He says that they don’t know how long he has to stay in the hospital and he wants to know how long you are in Laos, if you want to give him money now to pay for some expenses, then more depending on how long he has to stay.”

Jody peeked her head through the door.

“Don’t answer how long you’ll be in Laos!”

“He also says that he wasn’t drinking when the accident happened and because he works for the military, he doesn’t have to carry a license to drive a motorbike. His military status also means the police will side with him in any investigation.”

I caught the producer’s eye.

Is that a threat?

He wanted $1000. My jaw dropped. Cody and I had both been cleaned up at the hospital after our accident and been given loads of medicine for a grand total of only $16. Obviously this was different, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that well, Jack was being shaken down. Jack responded that he didn’t have much money, he was just a young traveler. He offered $400. Mr. Pathoummakong angrily gestured that that wasn’t enough to help with the damage. The room grew tense as the negotiations moved forward. Finally, he and his wife summed up the total costs for medical bills to be around $700.

There wasn’t really any arguing. If Jack didn’t comply, they wouldn’t sign the papers allowing him to get his passport back. And then he would pay thousands of dollars in court fees and visa extensions for a verdict that would most likely deem him guilty.

“I don’t have that much money, but I’ll try to see if I can get it. Will you tell them I need to figure it out?” Jack said. Phvong translated. The Pathoummakongs stared at him unhappily. As we filed back out of the room, I shook hands with the couple and bowed awkwardly.

I left the hospital feeling less relieved than I’d expected. I had that tight ball in my gut, the one that I always got when I felt like someone was taking advantage of someone else. Like all the concern I’d felt over the past few days had been taken for granted. Like Jack had been duped. We were the only ones that attempted to help the man when he was knocked out on the road and now here he was, extorting one of us for as much money as he could get.

Jody apologized as we left the hospital, informing Jack that she’d usually debrief him on “next steps” immediately, but The Embassy had asked her to wait until they’d reached a location where they could film it. You know, get a genuine reaction.

On the way to the provided location, the producer asked Jack if he could do a short interview during the drive, tell them how he felt about everything, act as if they were headed to the hospital instead of leaving it. Then they filmed us all staring contemplatively out the windows again. This time, nobody had to fake the pensive looks.

The debriefing happened at a fancy coffee shop in Vientiane that served real lattes, not just gritty drip poured over a base layer of condensed milk. They came out in fancy, clear glass cups that kept the coffee in a central tube so it’d never be too hot to hold. The filmed meeting was short and sweet. Jody and Phvong explained that everything had gone quite well and Jack said he was just glad the guy was okay, that he’d have to work out the money.

When the cameras were turned off, Jody remarked that it was unfortunate the family seemed less genuine now. That they’d changed prices of everything several times. That they were hoping they could squeeze as much money out of Jack as possible. I could see from the look on her face that she felt that same tightness in her gut as I did.

Later that night, Phvong called Jack, apologizing profusely as he told him he’d forgotten about the “police investigation fee.” Jack would also need to get out at least $200-300 to pay for those six hours we were detained outside of Nakam. The six hours of waiting while the officers sat around, ate, smoked cigarettes, and took turns hitting on me. The insult was incredible. It was like eating at an overpriced restaurant, enduring poor service from a bored, rude waiter, and then being handed a bill with gratuity already included.